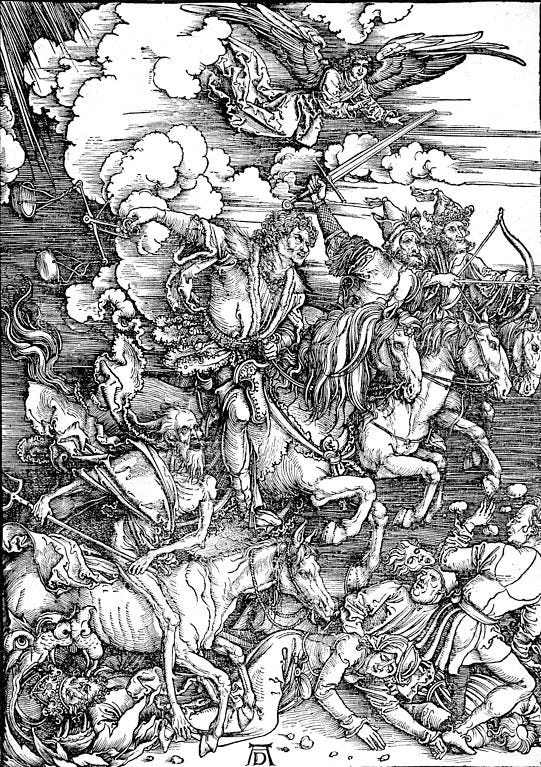

The Four Horsemen

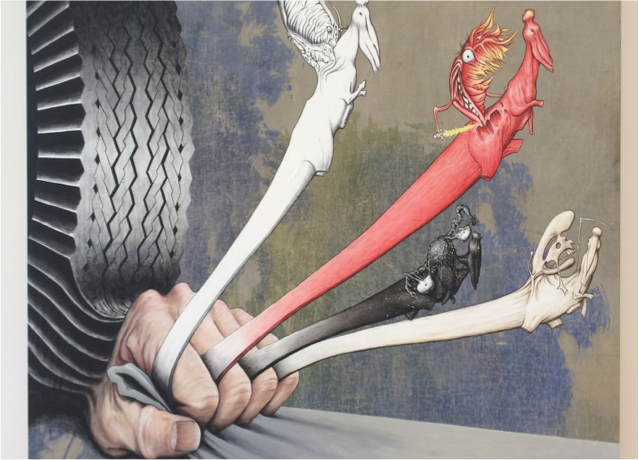

Here they are, the four horsemen of the apocalypse. One of my favorite modern artists, Jim Shaw, often playfully engages themes of apocalypse and exhibited this several years ago:

In Revelation chapter 6, a white, red, black, and pale green horse emerge, presumably from the heart of God’s presence. John of Patmos has taken readers on a sci-fi genre trip, with visions of creatures at God’s throne and the slain Lamb of God who alone can open a powerful scroll’s seals. With these riders of destruction, however, John decidedly veers into horror—or at least Game of Thrones—territory.

This is the junction where Revelation makes its violent turn, the place where many progressive rationalists drop the text and say, “No, thanks. I’ll pass.” It’s admittedly hard to stomach that ancient religions, even aspects of Christianity among them, were not exactly peaceful: in the surrounding Greek myths, Zeus’s dad Kronos eats his children and Zeus begins a “Clash of the Titans” by tricking Kronos to vomit his children up. For most of the New Testament, it is possible to prioritize history and avoid the weird elements of demons, powers, and angels. Not so with John’s Revelation. There’s no evading the cosmic struggle at play, and we seem clearly to be operating in an archetypal, mythic visionary realm. That’s one reason, among many, that the book is read and preached so little today. We don’t know what to do with visions.

These apocalyptic myths of cosmic war grip us, perhaps more than we acknowledge. American culture has not, after all, given up on such myths: conservatives take it literally, including hell, while much of us, religious or not, simply project the heavenly, world-at-its-end battle elsewhere into our collective consciousness, largely onto superhero films. The villain Darkseid in Zack Synder’s Justice League dwells on a planet called Apokolips. Thanatos, the Greek personification of death, shows up not only in the Avengers, but also in Revelation 6:8. This stuff is made for imaginations to soar and I’m convinced that psychically and spiritually, we still need apocalypse as a genre for sacred text. Our world is too violent not to have a myth that is able to hold the chaos of reality.

That’s what apocalypse does: it tells the truth about reality. It reveals or “discloses” what is previously hidden.

And this is exactly what’s happening with the four horsemen. Setting aside the fact that their genesis is from within the divine throne—I think we have to reject God’s causative agency for violence for this book to have any helpful relevancy for our lives—the four horsemen are primarily an assault upon the false myths of Roman imperial power. They are specifically referenced and written to critique, poke holes, counteract, and resist the violence of Rome. They reveal Rome’s violence, just as they reveal ours, which means that the four horsemen are not a threat for those who, like John’s hearers, already disbelieve Rome’s propaganda; but they are a threat for systems of domination. God is not the agent of judgment. We are. (Why did we turn God into the Punisher rather than the Lover? Our propensity to see a God of violence means that violence has been our god.)

Chapter five told of the scroll, the secret mail that God wishes to send. The nonviolent Lamb of God who has been murdered by the Empire is the only one deemed worthy to open it. The scroll carries seven seals that need to be broken before the contents of the message can be read. Each of the four riders rides after the opening of a seal.

I looked, and there was a white horse! Its rider had a bow; a crown was given to him, and he came out conquering and to conquer. —Revelation 6:2

Roman military leaders occasionally paraded after victorious battles on white horses, but what’s interesting here is the pairing of the bow and horse. Rome’s soldiers may have ridden horses, but they did not fight with bows. Outside powers on the edges of Rome’s empire did. The Parthians at the east, for example, were known for their skillful mounted archers and had conquered the Romans on a number of occasions. These riders are a threat, not to John’s hearers, but to Rome’s security. Commentator Craig Koester points out, “Instead of commemorating the Roman conquests that produced the relatively stable social setting in which they lived, the vision raises the specter of conquests that could threaten the prevailing order.” The attackers are directly calling into question the so-called “Pax Romana,” the peace of Rome.

And out came another horse, bright red; its rider was permitted to take peace from the earth. —Revelation 6:4

With this verse, John directly challenges the lie of Rome’s false peace. The prophet Jeremiah memorably criticized his own day’s court prophets for saying “Peace, peace” when there was no peace (6:14). Rome’s peace likewise masks violence. The social tranquility that some enjoyed during the Pax Romana was only possible because of the land-grabbing, crucifying, and enslaving that took place through Roman conquest. Similarly, the prosperity of the United States as a country was only made possible because of stolen land and labor. But Rome and America’s myths called it peace and prosperity—instead of conquest, genocide and enslavement—anyway. An altar heralding the Pax Romana said, “never had ‘the Romans and their allies thrived in such peace and plenty as that afforded them by Caesar Augustus.” (Strabo, quoted in Koester). But critics of the empire have always seen through the spin: “They rob, butcher, plunder, and call it ‘empire’; and where they make a desolation, the call it ‘peace.’ (Tacitus, quoted in Koester).

I write while the trial of police officer Derek Chauvin continues. Most readers know that his killing of George Floyd sparked a racial justice uprising and watershed reckoning with America’s racist past and present. Like the red horse, the Black Lives Matter movement “disclosed” the truth of American ongoing racism by puncturing the myth of “peace and progress” that so many white Americans have believed. But for those existing in the underbelly of the Empire, like John’s hearers, police brutality, mass incarceration, and poverty were not truths that needed to be revealed but systemic injustices that need to be changed. The apocalypse is good news for such hearers. It means that God has heard the cries of the oppressed and that change is on its way.

The third horse reveals the economic injustice of hunger; the fourth brings along Death and Hades (a son of Zeus’s father Kronos, no less!) to continue their ride across the earth. They have brought pestilence—further suggestion that the time of the coronavirus is indeed an apocalyptic time.

Vaccine availability is initiating much-needed surges of hope, but the end is still near (not literally, but mythically and experientially). God continues the work of revelation through apocalypse. Of all groups, the National Intelligence Council this past week released its Global Trends report outlining future possible scenarios for the next twenty years. From internal state conflicts, the collapse of nations, the rise of racist, nationalist movements, to climate-change disasters, we are living in a time in which catastrophe—for some people across the globe—is imminent at all times. This is why I believe the four horsemen (and the book of Revelation in general) are still relevant today. We cannot begin to change what is not working until the systemic problems are laid bare and the myths that support those same systems are revealed in their emptiness.

Image credits: Jim Shaw, Untitled, personal photo, MASS MoCA, Entertaining Doubts.

Albrecht Durer, The Four Riders of the Apocalypse, 1497-1498, public domain.

P.S. Does anyone wish to join me, my yoga teacher Georgia, and some thoughtful folks for an online book group to read Valarie Kaur’s See No Stranger? It’s one of the most impactful books I read all year, and I’d love to discuss with you.