Loving Broken Bodies

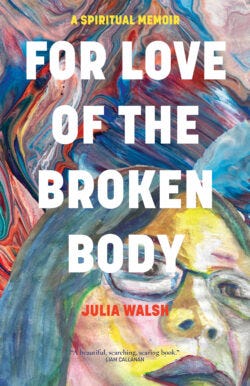

Book Review: Julia Walsh's "For Love of the Broken Body"

Sister Julia Walsh opens her book For Love of the Broken Body by telling in horrifying detail her plummet from a cliff. While visiting her family property during a period of discerning whether to join a religious order (Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration), Julia sets up her tent, finds a tree under which to journal in shade, spends time praying and, while attempting a swimming jaunt, falls down a precipitous cliff.

The book begins as a bloody thriller: “I’m alone, face down in a stream on the farm in Iowa where I grew up. My body is soaked. I taste blood in my mouth. What happened? Oh my God. I fell off the cliff, twenty feet onto the rocks. And I’m not dead.” After reading this first chapter about Sister Julia’s shocking, careening descent, I couldn’t put the book down. She guides the reader through that traumatic event and the aftermath: her time in the ICU, her broken jaw, facial reconstruction and recovery, the pureed food that her mother makes her, and the dedicated visits that her Franciscan sisters make to the hospital. But fairly soon after the first chapter, the real thrill of the book sets in, which is Julia’s vocational call to sisterhood (FSPA). The book is a spiritual quest told through the tale of a near-death experience.

So, this week I share a book recommendation. I read a lot of books, but most of them I skim and do not finish. I wish that were not the case, because I surround myself with so many wise and beautiful books that deserve to be read all the way through, but I can only do so much. The ones I do read until the end are books that engage me on an energetic level. That may sound “woo-woo,” but it’s true. The genres and writing styles may differ. The book could be Brian McLaren’s newest Life After Doom (a must read); the classic The Way of a Pilgrim, which I had never read before this year; Cole Arthur Riley’s magnificent Black Liturgies; or Palestinian Christian liberation theologian Naim Ateek’s A Palestinian Cry for Reconciliation, or Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperfield. I wait for an inner, compulsive excitement to propel me forward on the pages, something that tells me emphatically, “I have to read this now.” These days, if I don’t feel that inner impetus, I put it down. Life is too short. And Sister Julia’s book did that for me. It reminded me of the urgency of discovering one’s path to God and one’s place in the world, which I believe is a unique, beautiful and even harrowing adventure to which each of us is called.

Much of Sister Julia’s struggle around whether to join the sisterhood circles around the inherent celibacy required. In her path leading to formal religious life, she is very forthright about her various crushes on young men, and the vocational complexity that her desires create. Does her attraction for Mike—a male friend who shows up frequently and whose instant message chats (anyone remember those?) with Julia are folded into chapters—mean that she is intended to be a spouse or mother? Or is her sexual desire something to “sacrifice” in the larger cauldron of divine love through celibacy?

I suppose I connected with Sister Julia’s journey because of my own evangelical history of “purity culture” in which sex before marriage was strongly opposed and dating became a form of courtship. I recognized the awkwardness of pre-Franciscan sister Julia’s inability to tell Mike that she has a crush on him, and her agonizing, journaled prayers to God: “God! Good God! What is it going to take for me to ever have peace about relationships? Could I ever be able to do as I desire: see the beauty of people, thank you, bless them, and move on?” Walsh shows us that there is something deeply transforming about bringing all of our desires to God, whether one chooses a life of celibacy or sexual intimacy with another. And instead of the angst, body shame, and unhappiness that I carried in those years, I did not hear shame in Sister Julia’s story, just an authentic struggle with desire that leads to wholeness.

Walsh also undergoes her vocational quest in a similar time period as my time in seminary and living in a Catholic Worker-inspired community. It brought a lot of memories back. Julia is inspired by the progressive evangelical “new monastics” sprouting up throughout the U.S. and world in the 2000s, living in prayerful, intentional community with others and serving their neighborhoods in varied ways. I, too, visited Kensington, PA and other places to see what communities like “The Simple Way” were up to. Through her time in “Jesuit Volunteer Corps,” Julia captures the vibrant idealism embedded in the gospel, expressed through social action and radical commitment to helping those in need. She is drawn to “new monasticism” but also “old monasticism.” Eventually, it’s through the wider church tradition, the dedicated community of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, and the counter-cultural callings of “poverty, obedience, and celibacy” that Walsh finds her home.

Photo by Marianna Smiley on Unsplash

It's no surprise where the story is going. We know that Julia will become “Sister Julia.” But the healing process from the catastrophic fall, the heartfelt struggle with sexuality and celibacy, and the deepening love that Julia feels for herself, God and her Franciscan community draw the reader forward. Julia finally learns to accept her wounded, broken body: “I now love all these broken parts of me. Or at least I have grown to accept them, embrace them, allow myself to carry around these wounds as reminders of what I’ve survived, been through, of the miracle of God’s love that has reformed, reshaped, and reclaimed me.”

Walsh’s acceptance of her own broken body becomes an entrance into true solidarity and community. With striking wisdom, she shows that her broken body is not an aberration, but rather a mirror for the brokenness of all bodies, including Jesus and her fellow sisters: “This broken body I love is also Jesus… [and also] every human who held me in my misery, who tended to my wounds, who held my hand during surgery or sickness. It is the people of God…” Sister Julia’s authentic, broken quest invites all of us to embrace our own authentic, broken quest wherever we are.

Thank you Mark for this wonderful recommendation. I too am working on loving my broken body.

What a great review. I'm going to pick the book up right now!