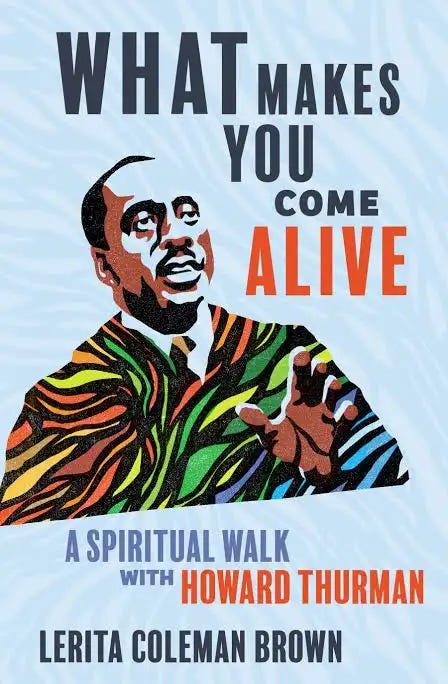

I learned this weekend that spiritual director and author Lerita Coleman Brown passed away. I didn’t know her well, but I had the grace-filled opportunity to speak with and learn from her a couple of times. Her work on Howard Thurman in her book “What Makes You Come Alive” touched my heart deeply. I share this previously released episode in honor of her passionate quest for aliveness. Here is the full, lightly edited transcript, even as I encourage you to listen to the episode to encounter Lerita’s kind and sparkling wisdom:

Introducing Howard Thurman

Mark: Today’s guest is Lerita Coleman Brown. She’s a retreat leader, a spiritual director, and the author of a wonderful book about the Black mystic theologian Howard Thurman. It’s called What Makes You Come Alive.

I really loved this conversation. Lerita has spent years studying the life and wisdom of Howard Thurman, and she shares her learning in a way that impacts our everyday quest for God. We talk about Howard Thurman’s nonviolence, his influence on Martin Luther King, Jr., how Thurman understood mysticism as a creative response to life, and more.

Lerita: Howard Thurman is such an extraordinary human spirit. I did not learn about him until later in my own life, and I was actually very shocked and dismayed because we were both in Northern California in the early ’70s, and I could have met him—but I knew nothing about him. As I began to read more about him, and as I started giving presentations about him, I came to understand that there were a lot of people who didn’t know about him either.

There was something in me that was deeply curious, but I also found him to be a very affirming figure, particularly with respect to contemplative spirituality. Howard Thurman was born on November 18, 1899, near West Palm Beach, Florida, but he grew up in Daytona Beach, Florida. He was a person who felt very connected to the outdoors and spent a lot of time there. He lost his father when he was about seven, and I think that loss may have driven him outdoors—to walk along the ocean or among the many trees there.

He was raised primarily by his mother and grandmother, Nancy Ambrose, a formerly enslaved woman who taught him that he was a child of God. She wanted that to be his primary source of identity, because she knew that as a young Black child—especially a Black male—he would encounter a very hostile Jim Crow South. She wanted his life and his thinking to be rooted in God.

Thurman spent much of his young life in Daytona Beach having what we might now call mystical experiences outdoors. He was also very bright and read widely, reading the Bible aloud to his grandmother. At that time, Black children could only attend school through the seventh grade, so the community gathered around him, arranged for private tutoring, and helped him attend the Florida Baptist Academy—now Florida Memorial University—where he was an extraordinary student and graduated valedictorian.

As a result, he won a full scholarship to Morehouse College here in Atlanta, where he again graduated valedictorian. There’s a myth that he read every book in the library during his time there.

He then felt called to ministry and was accepted at Rochester Theological Seminary, one of the few seminaries admitting Black students at the time. He had an extraordinary career there as well and again graduated valedictorian. Soon after, he married Katie Kelly, and they moved to Oberlin, Ohio, where his first pastoral assignment was at Mount Zion Baptist Church.

One night, while attending a meeting, he became restless, stepped outside, and picked up a book called Finding the Trail of Life by the Quaker mystic Rufus Jones. Thurman felt as though Jones had written his own life onto the page. Jones had also experienced mysticism as a child. Thurman tracked him down, sent word through a mutual contact, and Rufus Jones invited him to Haverford College as a special student for a semester to study mysticism.

Coming from a Baptist seminary, Thurman didn’t even know mysticism was a field of study. At Haverford, he encountered an affirmative mysticism grounded in the Quaker belief that God dwells within each person—and that when you go down into God, you come up in unity and community. This deeply moved him, and he later began to write about it, though he was often criticized because mysticism was widely misunderstood.

Thurman eventually began linking mysticism and social change. He believed God created a single, interconnected reality. When we have what he later called “creative encounters” with God, those moments should loosen whatever keeps us separate from others and send us back into the world to help restore God’s beloved creation.

He wrote the influential book Jesus and the Disinherited, offering a radical interpretation of the Gospels that inspired theologians and activists such as Bayard Rustin, James Lawson, Pauli Murray, and later Martin Luther King, Jr. It became something of a blueprint for the civil rights movement.

He founded the first intentional interracial church in San Francisco, spent six months in India in the 1930s where he met Gandhi, and later became the first Black faculty member and dean of Marsh Chapel at Boston University—where his life again intersected with King’s. It was truly an extraordinary life.

The Creative Encounter

Mark: I’d love to ask about the Gandhi pilgrimage and the impact that later set for the nonviolence ethic and direct-action practice in the Civil Rights Movement. But I want to go back to something you just said: that the creative encounter for Thurman was a way of describing mysticism. That’s really interesting to me, especially when I think about the holiness of ordinary life. Can you say more about this creative encounter—what it meant for Thurman, and what it might mean for us today?

Lerita: Well, Thurman was really searching for another word for mysticism, because mysticism has these associations with the occult, and people can feel uncomfortable with it. Even when I go around talking about Thurman, people will say, “Well, I want to know about this mysticism stuff,” you know?

So he was trying to find ways to describe it. As he writes, mystics have these extraordinary experiences of transcendence—maybe a vision, maybe a voice, maybe a burning bush. It can take many forms. And they come away with no real words to describe it.

So he thought, maybe we should call it a creative encounter—because these occurrences probably happen more often than people think. And it’s not necessary to live in a cloistered community or be a religious person in order to experience them. In fact, you don’t have to be a saint at all. You can be an everyday person who somehow has a transcendent experience—an encounter with whatever you would describe as God.

So he brought it out of the clouds a little bit. And we begin to see that there are lots of people who are mystics—though Thurman would probably have fairly rigorous requirements. He felt a true mystic is someone who has committed to living a life with God, and he says the true mystic “yields the nerve center of their being to God.”

Now, those of us out here having mystical experiences—I always tell people I’m kind of a mystic, right? But I think, like many others, I haven’t yet been able to give up all that control and yield the nerve center of my being to God.

Everyday Mystics

Mark: You’ve got this great phrase in the book—“everyday mystics.” I want to quote from the book for a moment. You say Thurman demystified mysticism by framing it simply—and I love it. You just explained it with the creative encounter.

Mystics are people who have a personal religious experience or an encounter with God, and he believed that anyone can be a mystic if they’re open to the experience. He opened a door to a world where mystics move freely among us and live ordinary lives.

Can you say a little more about how Thurman gives us that permission—to be everyday mystics, to have that creative encounter?

Lerita: Well, first, he modeled it in his own life. He may have understood very early that he was having these encounters. And then he meets Rufus Jones, who says, “Yes—I had them too as a child.” And then Thurman meets other people, even Gandhi—people who are living everyday lives but are deeply attuned to this Presence.

Many people who describe Thurman say he just exuded the Presence. He could walk into a classroom and still be communing, and his students would just sit there until he was ready to start talking. James Farmer, in his autobiography, says—almost humorously—yeah, we just had to wait for him to come back into the room.

But for me, I always thought I was a little bit weird—though I’m from California, so, you know, “woo-woo” and weirdness are more acceptable. Still, there weren’t many people I could talk to about my mystical experiences.

So when I finally discovered Thurman, I thought: Oh! I’m not crazy. I’m not the only person out here—who’s not in a convent—having these kinds of experiences: hearing voices, feeling a Presence come into the room.

And then I came to understand there were Black female mystics who preceded Thurman. There’s a lovely book called Sisters of the Spirit about three women who had similar kinds of experiences in the century before Thurman. And I suspect there are many more—we just don’t hear about them, because the word mystic has kept people in the closet, unwilling to share these experiences.

Nature and Presence

Mark: I know nature plays such an important role for him. Would you be willing to share how nature plays a part in his everyday mysticism—of opening to the Presence?

Lerita: Yes. Thurman believed the Presence of God was everywhere—but especially palpable outside. It was as if everywhere he looked, he saw something that created awe in him: trees, deserts, the way certain pines need heat to burst open their seeds.

I have a window here in my workroom, and I’m looking out at these naked trees aligned against a beautiful blue sky. How can you not feel awe? They’re not dead—they’re still alive. And it reminds me of God.

Thurman loved sunsets. One of my favorites, though, is stillness. He felt stillness as a boy walking along the beaches of Daytona Beach, or out in the forest. If you pause, stillness just embraces you.

In winter, I can walk into my backyard and pause and feel it. It’s extraordinary—and different from summer stillness.

As a child, I was drawn to the wind. I didn’t have a name for it, but I think what I was experiencing was the stillness that came with it—just pausing, and enjoying it. I didn’t know it was mystical or contemplative, but I was drawn to it. And I still love silent retreats—places where stillness can embrace you.

And I just want to mention—Thurman also liked rivers. He loved how they shape the rocks around them, and how they’re moving toward the ocean. He has so many metaphors around water and God and our lives. It’s just lovely.

Mark: I love the story you included about Thurman walking home from seminary one night. He’d never heard the sound of water on his way home, but that night he could hear it—was it a canal? Would you be willing to share that story?

Lerita: Sure. You’re correct—he was in seminary, and one night he was walking home later than usual. And he heard water. He couldn’t believe it.

So the next day he asked one of his professors, “Where was that water?” And the professor said, “Oh, there’s a canal underneath the street. But during the daytime—with traffic and noise—you can’t hear it.”

And of course he uses that as a metaphor for us. As long as there’s a lot going on outside of us—noise and chatter—we may not be able to hear the still, small voice, or hear the voice of God. But it’s always flowing.

Photo by antonio molinari on Unsplash

Mysticism for Everybody

Mark: I want to go back to what you said about Black women mystics—who wouldn’t necessarily be categorized as mystics. A lot of us think a mystic is someone who lived in medieval times, or in convents and monasteries. But what I hear you saying is Thurman offers a vision of deep spirituality that is for everybody—through all times and places, of all races and experiences.

Would you say more about how Thurman opens up that category? And if you’d like to share about the mystics you’re thinking of from the 19th century, go for it.

Lerita: Well, I think he normalizes mystical experience in some ways—and he links it to social change.

It’s this idea: you have these experiences of God, and as a result you come to know who you truly are—not what the world has told you, but who you truly are. Thurman would call it an accurate self-portrayal.

And that allows you to live more rooted in God—living from God—which gives you courage and strength to move against injustice.

So here comes the idea of the mystic-activist. When you go into God and consent to participate in restoring beloved creation—that means all of it. God has a role for you. Not everyone has the same role, but there’s one uniquely prepared for you. Maybe not just one—maybe a series of things over time.

And as he would say, you need meditation. He meditated under an oak tree as a young boy. Meditation becomes spiritual renewal—like plugging in and recharging with the ultimate recharge. We recharge our cars, our computers—everything has to be recharged. But what about us?

And he was clear: spiritual growth isn’t just for us. It’s for us to have the strength and courage to do what we’re called to do.

Now, the women—Jarena Lee, Zilpha Elaw, and Rebecca Cox Jackson—were called around the issue of preaching, when women weren’t allowed to preach. They defied the rules and preached anyway. I believe Zilpha Elaw went to Europe. But the call was preaching.

And what happens is you become a bit fearless when you’re living from God, because you know you’re going to be protected. Your life transforms—from pulling the cart yourself to being guided by Spirit: inspiration, direction, guidance. You don’t have to be ruled by what others say or do. You know your call, and you can be faithful to it.

Mark: So somehow that knowledge—being a beloved child of God—gives us the fearlessness to face oppression, hardship…

Maybe that’s a good time to talk about the Gandhi visit. Howard Thurman is often credited as the spiritual link of nonviolence from India to the Civil Rights Movement. He visits Gandhi in 1935–36. Could you say more about that visit—and how the teaching and discipline of nonviolence came back to the U.S. and impacted the movement?

Gandhi, Thurman, and Nonviolence

Lerita: Well, I’m going to step a little ahead and say there’s a lovely book called Nonviolence Before King, written by Anthony Siracusa. He shows that Thurman was writing about Jesus as a leader of a nonviolent religion in the late ’20s and early ’30s. He was preaching about it. He was encouraging students at Spelman and Morehouse not to let their spirits be terrorized by what was happening.

This is the beginnings of Jesus and the Disinherited. He published a paper before the pilgrimage called Good News for the Underprivileged. It was like a setup for what would later become his major work.

So Thurman and Gandhi were both thinking deeply about nonviolence. And I think meeting Gandhi solidified Thurman’s desire to come back and work on it more fervently.

Gandhi basically said: this is the only way, because love is the most important force in the universe. And he told him: start small—with little acts—and work your way up, and then gather a group to work their way up into civil disobedience.

Thurman came back excited and gave talks all over about nonviolence.

Now—the meeting almost didn’t happen. There’s a book called Visions of a New World: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to India about how it all came together. People were talking about bringing Gandhi to the United States, but they feared he’d be assassinated. Others thought maybe they should visit him.

Thurman originally didn’t want to go, because he wasn’t going to proselytize Christianity. Indian people really challenged him on that—because some Christians in India wanted someone who “looked like them” to come over and make Christianity look good. Thurman wasn’t interested in that. He knew Christianity had been in India since the third century.

But he was convinced it could be worthwhile—especially the chance to meet Tagore and Gandhi. And he said he’d go as long as he could take his wife. And another couple went as well. They spoke about many things, not just Christianity.

At a law school early on, a dean—or someone—really challenged him: “What are you doing here? Why are you even here? How can you call yourself a Christian?” He listed segregated churches, lynchings—people going to a lynching and then going back to church. All of it.

And Thurman said: “Actually, I’m a follower of the religion of Jesus.” That was big. He was saying: I don’t know what these other people are doing, but I’m paying attention to what Jesus was doing—and I’m trying to live that.

Someone had the wherewithal to take notes during the meeting with Gandhi, so we have a record.

Gandhi was interested in the progress of Black people in the United States, and Thurman gave him a Black history lesson. And Gandhi said something remarkable: that the unadulterated message of nonviolence would come through the American Black population.

There was another person—Benjamin Mays—who visited Gandhi in the 1930s. So there were multiple threads.

And I really do believe the Spirit was orchestrating all of this.

Here’s one of the things I discovered: Thurman’s first wife died of tuberculosis. Then his second wife, Sue Bailey Thurman—and Alberta King (Martin Luther King Jr.’s mother) were roommates in high school.

They were roommates. So when the Thurmans came back from India, one of the first places they visited was to have dinner with the Kings. Martin Luther King Jr. would have been about seven at the time.

Then King encounters Thurman again through Jesus and the Disinherited—and King actually wrote a paper on it. Then they cross paths at Boston University. King would attend Thurman’s sermons and take notes.

And when King was stabbed in 1958 by a mentally ill woman, Thurman started having visions of him—his face kept coming to him. Thurman told his wife, “I have to go talk to him.”

He went and said: “This segment of the movement has taken on a life of its own. And I hope as you recover, you’ll take time for silence and stillness and solitude, so you can understand what your role is going to be.”

He said it’s the only time King took any time off.

And that’s why I tell people: I think the Spirit is trying to orchestrate things for us, but we get in the way.

Fellowship Church and Communal Silence

Mark: I want to ask you about Fellowship Church, too. He has this tenured position—he’s a professor at Howard University—and then he gets involved in this invitation to start the nation’s first interracial, interfaith church in San Francisco.

What struck me so much—reading one of his books on this, I think it was Footprints of the Dream—is that he really believes collective worship and spiritual experience can be a unifying point for people of different backgrounds and life experiences.

Would you speak about how unique—and risky—this was in the 1940s, and what it was about contemplating together that was so powerful for him?

Lerita: Thurman really was a man of God, and of deep faith. And two things happened.

One: in India, he had a vision at Khyber Pass, and he felt called to test this idea that people from different faiths, different racial and ethnic backgrounds, could come together in the same space to worship God.

Two: his semester with the Quakers. He attended Quaker meetings—unprogrammed, unscripted—where people sit in silence. He describes sitting on one side of the room with his own noise, while others were communing in the Presence. And at some point, he said he wasn’t Howard Thurman anymore. He was a human spirit joined with the rest of them in communal connection.

So he began introducing silence in worship—first at Howard University, and later more deeply in California. People wanted more. So there was a silent period during worship, and he also created a period before worship. That’s when he wrote many of the meditations we see in his books. People would come early and sit together.

And he said that when he added that second time of communal silence, requests for pastoral care went down. He believed something in the stillness helped illuminate people’s minds so they could understand their own struggles more clearly.

I believe communal stillness is powerful—and healing.

Mark: And if you can imagine—this isn’t a small group of twelve people. This is, what, 200 people at a time?

Lerita: Exactly.

Mark:

We don’t see that a lot today. And this was early 1940s, when he founded Fellowship Church?

Lerita: Yes.

Mark: Way ahead of his time. I’m also hearing it connect back to that fundamental insight: identity in God—beloved child of God—as a force for aliveness and power. Think about what you were taught about yourself, or what your self-concept was like, and how that changes when you can internalize: “Oh no—you are a beloved child of God.”

Aliveness

Mark: What does aliveness mean for Howard Thurman? He uses that word, and it’s in your title, What Makes You Come Alive. Especially for everyday people discovering divine presence and stillness—what does aliveness mean?

Lerita: Well, I was a college professor for 33 years, and sometimes I’d sit with students trying to help with vocational choices. And often I saw: when a student came across something that allowed them to live out their passion, they lit up like a Christmas tree.

So I think in the quote—“Don’t ask what the world needs; ask what makes you come alive”—there’s something in us connected to what we might call a sacred call. When we do it, we feel joy.

I describe it like winter turning into spring—everything that looks asleep wakes up, and it’s more alive than it was before.

For Thurman, to live fully—to come alive—is to be intentional about asking, praying: what is my sacred call? And then answering it.

For me, being a professor was wonderful. But spiritual direction—companioning people—makes me come alive in a different way. Writing this book was labor, but I felt so alive writing it.

For someone else it might be making cupcakes, or reading to children. We need to do some of that every day—discovering what helps us come alive, and doing it.

And as I told someone the other day: it’s really hard to get out from under the influence of the world. People get caught up in it. They may have all the material possessions they want, but they’re still not alive.

Mark: It’s back to that flowing canal—whether you’re paying attention to it or not. So much in our lives distracts us from attending to that flowing aliveness and Presence.

Closing

Mark:

I want to thank you for this rich conversation. I appreciate you sharing your wisdom with me and with listeners—and again, for giving so much of your life to learning from Howard Thurman and pursuing this journey of aliveness in yourself, so you can share it with others. You’re helping the rest of us become everyday mystics, too.

Lerita: Well, I hope people will feel freer to be who they are.